W. Edwards Deming’s Systems of Profound Knowledge has been a cornerstone to successful lean deployment for the last 20 years (longer, if you consider that it began with his 14 Points for Management). As written in an earlier post, I am a strong believer that the level of success with lean is directly related to the level of understanding and application of Deming’s system of management.

The four components of Profound Knowledge as presented by Deming include Knowledge & Learning, Appreciation of a System, Variation, and Psychology.

Deming rightly presents the need for leaders to have an appreciation for psychology because of the fact that effectively leading requires knowing how to relate to people. Although it should be obvious, I have run across many people in leadership positions over the years who were severely short of people skills. There are differences in people and effective communication and motivating individuals requires understanding and working with these differences.

How About Sociology?

One aspect of leadership I always felt was missing from Deming’s system is sociology. Organizations consist of a number of individuals and teams, and in addition to knowing how to relate to and motivate people individually, leaders need to be able to continually develop and improve teamwork. This can not be done without an understanding of sociology.

There are natural and cultural forces within people that drive them to identity strongly to the teams to which they belong. Although these forces can be beneficial to improving performance, they can also be destructive to the organization, as a whole. It is all too common for people to put the needs of the immediate team ahead of those of the company. Even if this is unintentional – which in most cases it is – it is still very toxic to the company’s culture.

Maintaining a Unified Focus

One of the basics of organizational sociology is tendency of a group to break apart when its members start developing conflicting interests and objectives. Competition between factions develops and the ability to keep people focused on a common purpose becomes difficult, if not impossible.

Without strong leadership and an understanding of group behavior, internal competition (or apathy toward those outside of the immediate team) can grow to the point where correcting behavior can be extremely challenging.

Many leaders do not recognize the complexity involved in the individual and team goal-setting process. In far too many instances, there is too much going on to take the time necessary to assure objectives are aligned and well understood by all involved.

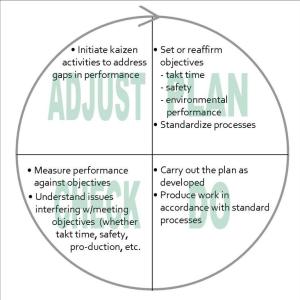

Catchball, a process for communicating direction, expectations, and objectives between levels in the organization, is critical to assuring that consistency is maintained and people work toward the achievement of a common purpose. Unfortunately, catchball takes time and, without a respect for organizational sociology, will not help prevent competition from developing and sub-optimizing performance.

Although sociology is apparent throughout Deming’s writings, I believe elevating it to the level of importance assigned to psychology, variation, knowledge, and systems thinking would help more leaders understand how critical it is to organizational success.