Structured problem-solving requires an internal reprogramming for most people. Fighting the urge to move ahead without clearly understanding the problem, breaking down the issue into smaller problems to better understand the situation, and developing a logical root cause based on the 5 whys are not things that come naturally to most people. Because of this, developing problem-solving skills requires changing the way people think rather than merely teaching them a new tool. This is difficult when the person is willing to change, but most people are not, which makes the effort even more complex.

In my experience, I have found four main issues that lead to poor problem-solving in an organization. I’m sure there are more but understanding these four will at least provide some direction regarding where to focus when the culture is not transforming the way it should.

1. Most people think they already know how to solve problems. Helping people understand and apply structured problem-solving is not as simple as teaching the steps and letting them go solve problems. Most people think they have been doing a good job solving problems for years and do not feel they need to change. For many of these people, however, problem-solving means adding inspection when a defect occurred, firing an employee who wasn’t performing, or pressuring suppliers to reduce prices when costs got too high. They felt good about these things because it showed they acted quickly and appeared to directly addressed the problem. Unfortunately, their actions mitigated the symptoms and provided temporarily relief rather than solved the problems. Helping people understand this requires getting them to realize something they have done in the past – and likely still do – was incorrect. This is not easy to do and requires building trust, a good deal of communication, and the ability to challenge effectively. To compound the problem, there is no one-size-fits-all approach to helping someone transform the way he or she thinks and approaches problems.

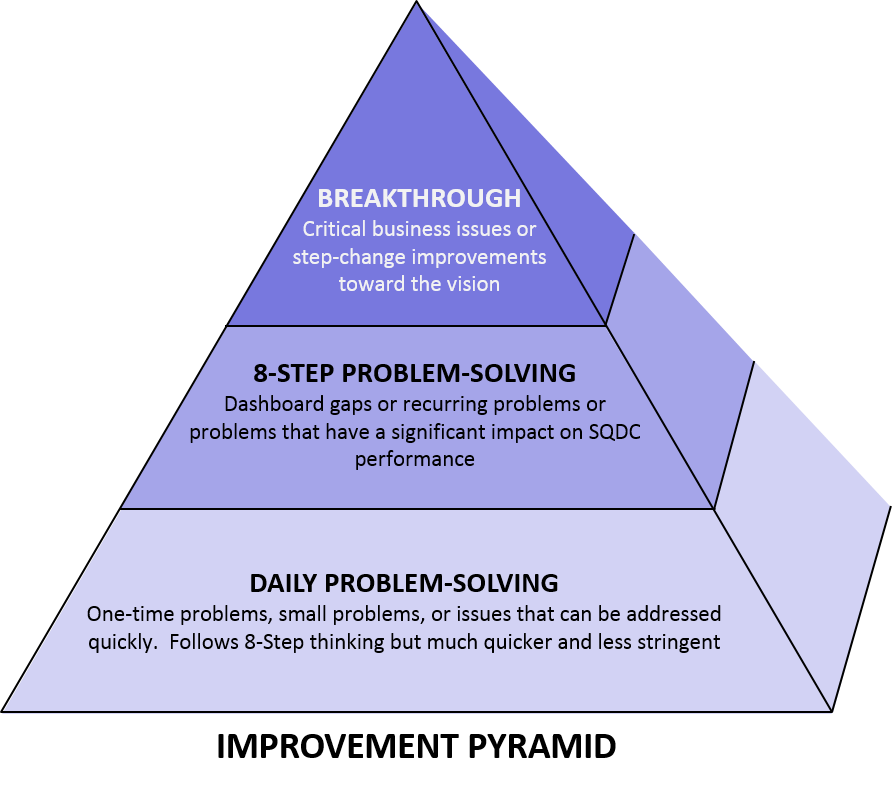

2. Many lean professionals and consultants don’t understand problem-solving well enough to drive change. It is unfortunate, but many of the people charged with driving the change in thinking do not have a clear enough grasp of problem-solving to make it happen. This tends to result in a heavy emphasis on the simpler tools to drive the transformation and, although they may show some early improvement in results, the ability to sustain them or address the truly significant problems facing the organization never happens. Another sign identifying a knowledge gap in those facilitating the effort is the tendency to address every problem with an A3 when, in fact, most problems do not require this level of effort.

Selecting someone to facilitate a lean transformation is a very important process. One way to improve the chances of success is to show the candidate a critical problem the organization is facing and asking how he or she would address it. If the candidate cannot quickly and clearly provide the approach, including the role that coaching would play, he or she likely lacks a deep enough understanding of structured problem-solving to be successful.

3. A lack of patience and persistence in driving the change. Changing the way people think takes time and persistence. Failing to understand this and expecting quick results will lead to failure. Even the small, one-time problems that do not require an A3, for example, still require structure. The objective in developing problem-solving skills, regardless of how simple the problem, must be focused on helping people learn the process, which includes clearly defining problems in terms of not meeting a target or standard and conducting a 5-why exercise to logically determine the potential root causes, and the more you can do this with small problems, the more people will be able to apply it to larger, more complex issues later on.

4. Leaders do not support the change. Addressing an issue like this would not be complete without mentioning the “L” word . . . leaders. Leaders must be closely involved in the transformation and learn structured problem-solving themselves if the effort is to have any chance of succeeding. They must learn it deeply enough to become the teachers and, most importantly, model the behavior when facing problems. Asking people about the expectation or standard that was not met when a problem occurs and following a 5-whys approach to guide the conversation when someone jumps to a countermeasure must become a normal leader behavior.

DIFFICULT BUT NECESSARY

Although critically important, developing effective problem-solving skills throughout the organization is not an easy thing to do. Success requires a coach with a lot of experience in solving problems and a good understanding of human behavior. It is something that must be done face-to-face where the problems occur rather than in a training class or conference room. Although not easy, when the team starts to develop a good understanding of structured problem-solving, the pace of transformation will accelerate. Even the "simple" tools like 5S start to have more meaning to people as they see how these things connect to the other tools and elements to improve quality and the flow of work.