One of the elements of lean that seems simple but is often misunderstood is the development and use of dashboards. People are often surprised to learn that there is a science to creating an effective dashboard and that it consists of much more than posting metrics related to the area.

A dashboard should drive development of people and improvement in performance. If these two things are not happening, then it needs to be changed. Too often, I find that the metrics on dashboards are oriented toward providing information to management rather than providing the team with the type of feedback that helps drive improvements. If the team does not find value in the dashboards, then it is waste.

ANATOMY OF A DASHBOARD

I approach the development of dashboards by initially questioning the team about the value it provides and the problems it encounters. Clarifying the team’s purpose will help it zero in on the value it provides to the process and what it should measure to assure it is helping the organization achieve its objectives. It also prevents the team from becoming too narrowly focused on one target while ignoring others that are just as important (e.g., a supply chain team focusing on the price of incoming materials rather than the total cost of the material, which includes the effects the material has on production).

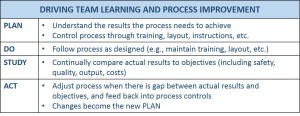

One thing to keep in mind with the process is that it requires time to reflect and truly understand what is happening with the process. Once the team purpose is clear, people can start to develop the metrics that will help drive the type of improvements needed to contribute to the organization’s success through the following steps:

- Define lagging metric targets: Lagging metrics measure of the result of a process. Defining the targets in terms of key areas like safety, quality, production, cost, etc. help measure what is ultimately important for the team. The lagging metric connects the team’s work to the larger system and provides feedback regarding the success of improvement efforts;

- Develop leading metrics: The leading metrics are the predictors of the lagging metrics in that they help to identify what is happening now that will eventually affect the lagging metrics.

- Identify activity-based leading metrics: Since some leading metrics are really lagging metrics, it is critical to work toward activity-based leading metrics, which measure what the team is actually doing to close the gaps in lagging metrics. The activity metrics are, in effect, the team’s efforts to solve the problems that show up in higher-level lagging metrics.

The figure below presents a very simple example of a safety dashboard for a rotor assembly area of a factory. The top of the dashboard provides information about the longer-term direction of the company. Although this may seem obvious to some, it is important to always maintain the connection between the team’s efforts and the company’s vision.

The next level of the dashboard provides what the company determined to be its ultimate measure of safety, followed by the rotor assembly team’s performance and focus for improvement. In the example, the team determined that it needed to reduce hand injuries in order to improve its safety performance and further decided that it will conduct regular audits and provide ongoing training to team members on a variety of hand safety issues.

The benefit of this dashboard is that the team can use it to identify the gaps in safety performance and actually measure what it is doing to improve. If safety is not improving, the team can look to the activity measure and figure out why, for example, audits are not being conducted according to plan. Team members can take action to assure audits are conducted as planned to ultimately determine whether or not they are driving improvement as expected.

The development objective of the dashboard comes from the conversations around the dashboard. How is the team performing? What are you doing about the gaps? Why are you focusing on hand injuries? Etc.

The effort takes quite a bit of coaching and reflection by the team to truly understand the process and how to improve to achieve targets. Once everyone understands that the customer of the team’s dashboard is the team, it becomes much easier to develop one that actually helps drive improvement.