Just like learning tennis or golf, improving the ability to solve problems requires three basic elements: (1) the desire to learn; (2) an effective coach; and (3) a lot of practice. This post will focus on the second element, coaching, and how to identify areas in a problem-solving effort where coaching is needed.

Before digging in to specifics of how to identify the gaps in a problem-solving effort, it is important to note that I use the term “solve” for convenience only because one can never be certain that a problem is truly solved. The best anyone can do is develop and implement countermeasures that appear to address the current situation in a structured and fact-based way.

The Red Flags

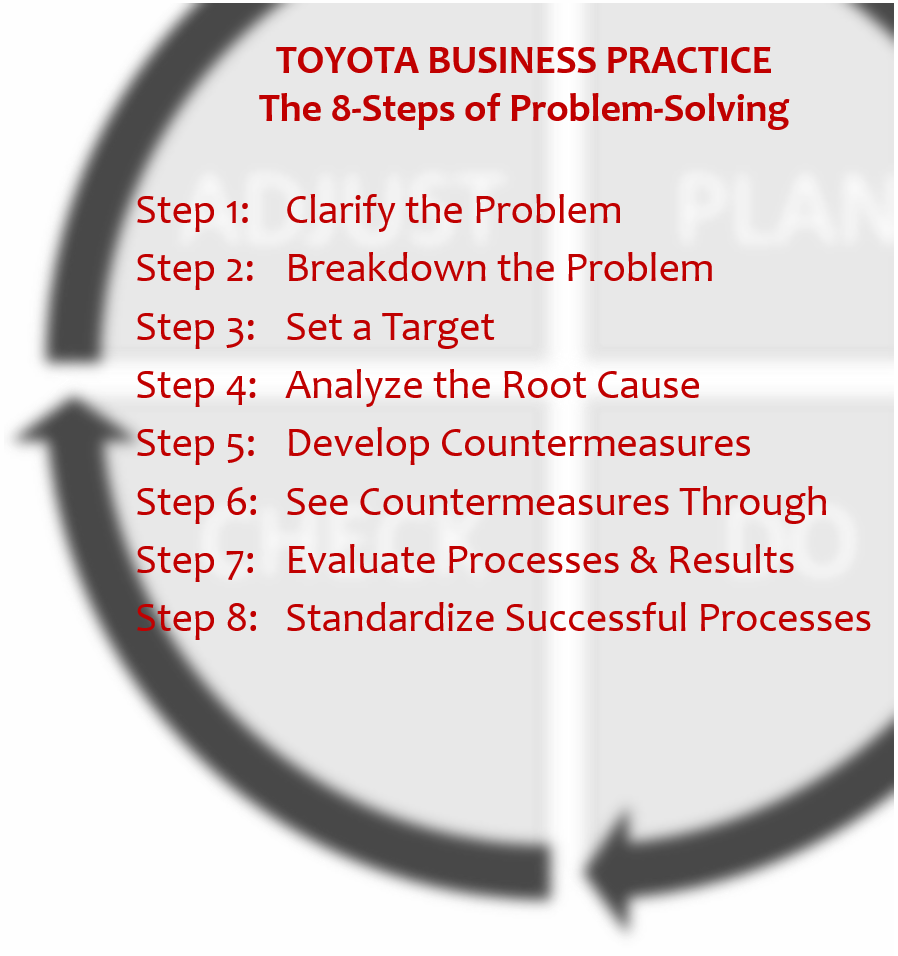

The red flags of a problem-solving exercise are based on the Toyota Business Practice (TBP) 8-step problem-solving process (shown above) and uses the A3 to identify the coaching opportunities. Detailed explanation of the 8-steps is readily available on the internet and in numerous books on lean thinking, so I am going to focus more on helping a person or team understand where the effort could be improved.Whenever someone asks for input on a problem-solving A3, I tend to look for the red flags or areas in each section where help is most commonly needed. The key is to help people understand that the process is about investigating, reflecting, and learning, not filling in the form. It is far too common, especially early in a person’s development, to force fit information into the boxes just to appease someone else and show that the process was followed. The coaching effort must help people realize that following each of the steps as intended will lead to learning and developing countermeasures that have a high likelihood of success. I also keep in mind that, although there is no “right” answer to addressing a problem, there are definitely wrong answers, i.e., those not based on facts and gemba visits. An effective A3 is easy to follow and clearly demonstrates that learning occurred between each step as the team zeroed in on the cause and countermeasures.

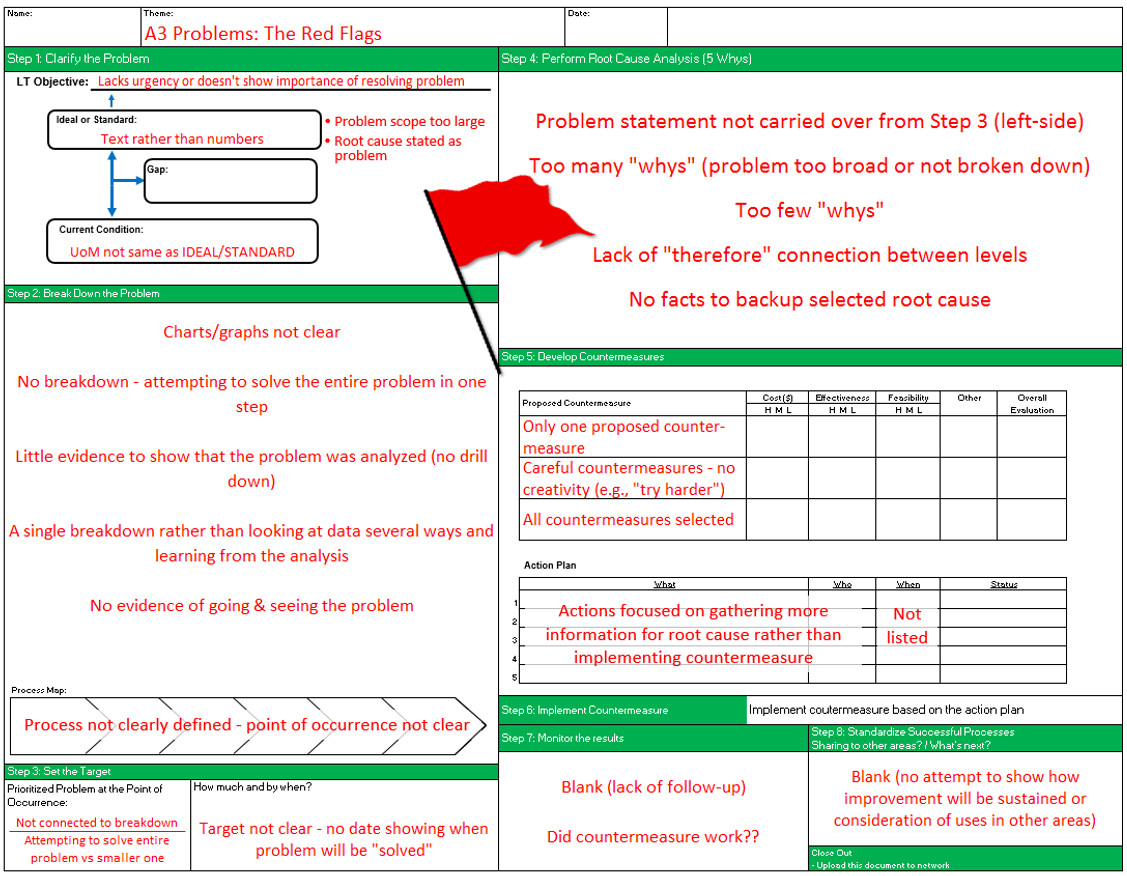

The figure below is a problem-solving A3 template with the red flags noted in each section. For additional descriptions of the potential problems listed, refer to the summaries of each step below the A3.

Step One: Clarify the Problem

It is difficult to argue that one step in the process is more important than the others but, since each step builds on the previous step to develop the story, any problems with the first box greatly interfere with the rest of the effort. One of the most common issues that shows up in box one includes failure to show the importance of the problem by ignoring the connection with higher-level objectives. Another common problem is using a lot of text to define the problem rather than a simple description or numbers. There is generally an inverse relationship between the amount of text on an A3 and the quality of the effort.Many people also tend to confuse a root cause with a problem statement. The problem is the basic issue that initiated the effort and is usually stated in terms of a lagging indicator, which must be clearly understood to get to the root cause.

Step Two: Breakdown the Problem

The breakdown of the problem is where the issue is dissected in order to better understand what happened and focus on the most important element to address. This is difficult for many people because of the desire to solve the entire problem rather than a smaller, more focused issue. It is important here to understand all the issues related to the problem so the highest priority can be addressed first. After the most important issue is solved, the team can return to the next most important issue, thereby chipping away at the problem.Step Three: Set the Target

Since the information in each step builds on the previous one, there should be a logical connection between the breakdown and setting the target. It needs to be clear why the team selected the problem and target and it must be based on the information and analysis in step 2.Step Four: Determine Root Cause

In this step, it is critical that the team starts with the problem exactly as written in box 3 to maintain the logical thread between steps and that the effort is based on facts and the knowledge of those closest to the relevant process.Step Five: Select Countermeasure

The biggest problem in step 5 is listing a single versus multiple proposed countermeasures – often a clue that the team had the answer in mind when they started the effort. Truly following the process requires the team to reflect on the root cause when determining possible countermeasures. When this happens correctly, there are usually a couple alternatives from which to choose.Also, the action plan should be related to implementing/testing the selected countermeasure. Often, the action plan hints at collecting more information to verify or determine the root cause rather than specific steps to address the root cause. If this is the case, the team needs to return to step 4 to better define the root cause.