“The basis of the

Toyota production system is the absolute elimination of waste.” – Taiichi Ohno

Every now and then, I like to go back and reread books I’ve

read in the past to be reminded of important points that I’ve either forgotten

or just missed the first time around. This

is particularly true of books by, or related to W. Edwards Deming, Peter

Drucker, and Taiichi Ohno. Recently, I reread

Ohno’s The Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production. Each time I read this book, I get a better

understanding of the thinking behind the development of TPS, including how I

can address a number of organizational problems I face that I’ve been unable to

resolve.

This time around, though, there was one point that kept

coming up and I couldn’t get past.

Throughout the book, Ohno repeats the idea the TPS is completely about eliminating

waste. The issue I had with this is

that, in my experience, people who focus lean efforts only on waste tend to get

overly focused on the tools and end up working a number of disconnected

problems that result in little sustained improvement.

A more subtle message in the book that I don’t believe gets as

much attention as the elimination of

waste is the challenge that Kiichiro Toyoda put forth regarding the need to

“catch up with America in three years.” Ohno

writes very fondly about Toyoda, including how important he was to Japanese

industry and the development of TPS. He

credits Toyoda’s statement as being inspirational, but rather than being the

drive for the development of TPS, translates it into a call for the elimination

of waste.

So Much More than

Waste

Perhaps Ohno’s view of waste is more complex than most

people can truly comprehend, but I think that the message of using lean to

reduce waste has gotten so watered down that most companies fail to achieve the

big gains that a true transformation can achieve.

When the focus is waste reduction, lean can easily become a

toolbox to reduce costs. In my

experience, every organization that turns its lean effort toward cost reduction

fails to sustain the improvements and eventually drops the effort when something

else draws its attention.

I contend that the focus of lean should be the company’s

vision. This assumes that the

organization has a vision and that it’s truly inspirational. In Toyota’s case, the vision was to catch up with America. Other companies that have been successful

with lean tend to have equally inspirational vision statements.

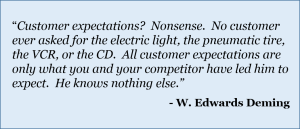

Deming said that a company’s vision is a value judgement and

must include plans for the future. This

means that it includes much more than profits or share price. It must relate to providing better and better

value to the company’s stakeholders, including customers, employees, suppliers,

the community, and shareholders. It is the

focus on improving the value to all stakeholders to a level never before

achieved (or even conceived) that provides inspiration.

When the organization has a clear statement that inspires

people, lean becomes the vehicle to make it happen. It provides a method for everyone in the

organization to align efforts and work together to drive sustained and

never-ending improvement. The effort

begins with the vision and translates it into more and more detail as it works through

the company’s long-term objectives, annual plans, dashboards, meeting rhythm,

and daily problem-solving.

It is through the alignment of these efforts, beginning with

a clear and inspirational vision, that lean enables innovation and an obsessive

focus on closing the gaps that are truly important to the organization. And when lean efforts are anchored by the

vision, people will not be distracted by the numerous management fads that can

derail the effort.

What Did Ohno Mean?

We’ll never get inside of Ohno’s head to understand whether

or not the vision of catching up to

America in three years is what truly inspired the development of TPS. It is only my interpretation that the vision

is what leads to sustained gains and what drives lean at Toyota. Perhaps I’ll see this more clearly the next

time I read the book . . . or perhaps I’ll find something else I completely

missed this time.