Although lean is based on the concept of continually improving to the point of perfection, many people have trouble understanding what perfection really means to their jobs and the company. They know too much to think the company could ever reach perfection. After all, humans aren’t perfect so why would we ever think an organization could reach an ideal state?

Breaking the Path to Mediocrity

In reality, a company will never reach perfection, but without a picture of what perfection looks like and continually challenging whether activities help or hinder the move toward the ideal, the company's improvement efforts will be mediocre, at best.

The more you clarify and emphasize the ideal condition in real terms, the better your chances of getting people to work together to move toward it. Although you most likely will never consistently achieve the ideal, keeping the organization moving toward it will get you a lot closer to it than just letting things happen naturally.

An excellent example of an ideal condition appeared in a recent FORTUNE article (link) about Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer. In the article, Meyer stated that she wants to make Yahoo, “the absolute best place to work.” Is Yahoo recognized as the best place to work today? If you can trust media reports and glassdoor.com, the answer is no. Will Yahoo ever get there? Maybe or maybe not, but if Meyer is serious about the statement as an ideal condition, she and her team will begin to implement changes that will greatly improve the company’s workplace and reputation.

In another example, I used to work with a company where the order-to-shipment lead time for the main product line was 23 days. Customers did not like waiting so long for the product but, since our quality was good and our competitors were delivering no faster than we were, our sales volumes were okay.

Recognizing the potential increase in revenues we could get if we reduced our lead time, I defined the ideal condition as same-day delivery for the product. I knew this was a huge stretch for the plant, given the current long lead time for the product, but I wanted to set a clear direction for improvement activities. To assure that changes represented true improvements, I also made it clear that reducing the product's lead time did not mean increasing costs, lengthening the lead time for other products, or reducing quality levels.

Some people had trouble taking the idea seriously but most bought into the idea right away. We began to track product lead time on a daily basis, discussed it in all planning meetings, and posted the metric in several places throughout the workplace.

Within one year, the product's lead time was reduced to 12 days. Besides a 23% increase in revenues, the improvements that enabled the reduction in lead time also led to decreased costs and improved quality in other product lines as well.

It's About the Gap

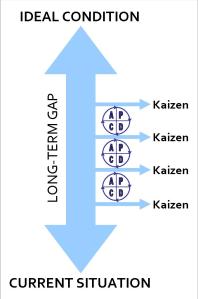

Once an ideal condition has been identified, the next step is to determine the current situation, or where the process, system, or organization is relative to the ideal. The difference between current and ideal is the gap to be reduced rough improvement activities.

The idea is not to attempt to close the gap in one step. Attempting to take on too much in one step can lead to frustration and disappointing results. Instead, kaizen activities should become focused on chipping away at the gap, moving toward the ideal at a continual and steady pace.

Success in business obviously requires much more than merely identifying the ideal conditions, but doing so provides the guidance that is invaluable for improvement activities. When a leader defines the ideal as something he or she truly believes in, provides the tools and method to enable improvement, remains patient, and gets out of the way, the results can be stellar.